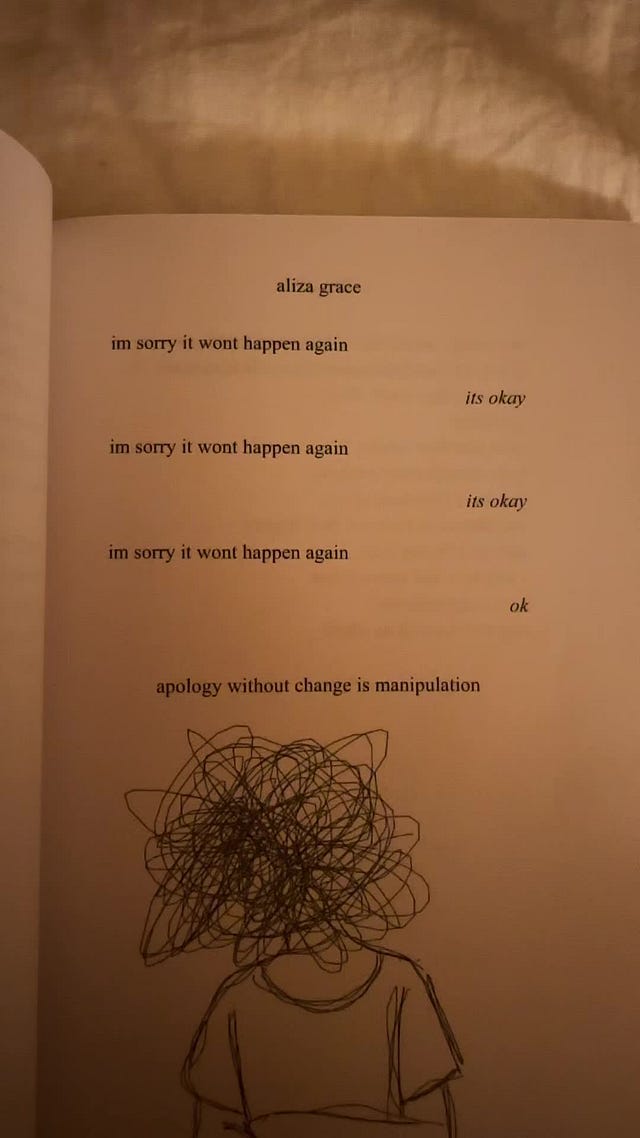

We’ve all seen them: those vague, bite-sized bits of advice broken up into separate lines and accompanied by an aesthetically pleasing illustration. Though claiming to be a poem, it looks more like a dissected tweet, a digital knickknack designed specifically to complement someone’s Pinterest board. If you’re a somewhat-pretentious-and-highly-individualistic writer like me, you may have just scrolled by and scoffed about the work’s lack of substance.

It’s likelier, though, that you read the poem and enjoyed it. That you found its directness impactful and its illustration charming, maybe to the point where you reshared it yourself. You wouldn’t be alone. The subgenre, dubbed “Instapoetry” from its origin on Instagram, is one of the most successful forms of poetry today.

Instapoetry’s short, visual nature allowed for its wildfire spread across various social media sites, but most recently TikTok. Though the subgenre may have began on Instagram and Tumblr, it has cemented its place in the literary world with its slew of published poetry books and handful of prestigious awards.

For as much success as the genre has enjoyed, it’s received even more criticism. The poems, often free verse and rarely longer than one or two sentences, have been called shallow and lazy. The style of writing itself is easily parodied, to the point where I was struggling to decipher which Instapoems were legitimate and which were a mockery when looking them up. Though, the critique most frequently tossed out tends to be “this is not a poem.”

I’d be lying if I said I didn’t agree, at least partially. As a self-proclaimed poetry enthusiast, I can’t help but find Instapoems to be uninspired and lacking in any real poetic qualities. They’re often just a few words long and rarely contain the use of rhythm or meter or creative wordplay. But, then again, poems don’t necessarily need rhythm or meter–the entire subgenre of prose poetry is testament to this. Neither do poems need to span multiple pages–haikus and cinquains are just a few universally recognised forms of poetry that are never longer than a few lines.